How is sound used to find submarines?

US Navy Submarine USS Key West conducting surface operations. (U.S. Navy Imagery used on this website without endorsement expressed or implied.)

Submarines have a unique advantage over other types of military vessels because they are able to stay hidden below the sea surface. One way of detecting and locating submarines is by using passive acoustics or active acoustics.

The objective of passive acoustics is to detect the sounds produced by a submarine, such as propeller, engine, and pump noise. These sounds can be identified by experienced sonar operators. Each type of submarine has a unique sound profile that makes up the acoustic “signature” of the vessel. Submarines themselves are equipped with passive sonar systems, such as towed arrays of hydrophones that are used to detect and determine the relative position of underwater acoustic sources.

The SOund SUrveillance System (SOSUS) is a network of passive acoustic hydrophone arrays on the seafloor. During the Cold War, early in the 1950s, the U.S. Navy placed SOSUS arrays in strategic areas of the continental shelf in the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans to listen for submarines (see History of the SOund Surveillance System). The hydrophone arrays are connected to shore stations where the acoustic data are analyzed. Initially, SOSUS was very successful in detecting and tracking the noise produced by Soviet submarines. In the early 1980s, it was estimated that SOSUS was capable of determining the location of a Russian ballistic-missile submarine with an accuracy of 93 km (50 nautical miles) or less.

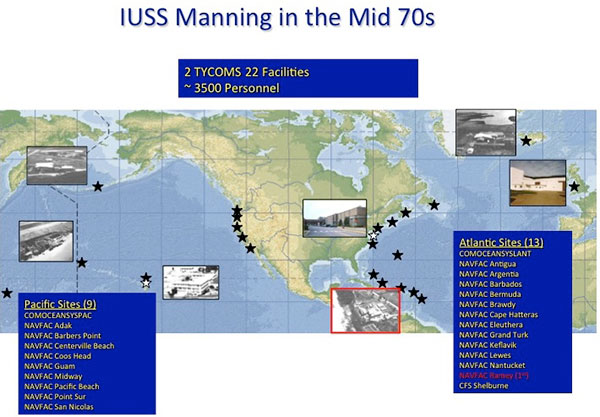

SOSUS in the mid-1970s. The black stars represent NAVFAC sites; the two white stars represent the Ocean System Commands. Image courtesy IUSS-CAESAR Alumni Association (https://www.iusscaa.org/).

In the 1980s, the network of fixed arrays was augmented by acoustic surveillance ships deploying the Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System (SURTASS), which is a towed line array over 2,400 m (8,000 ft) long. Because they are used on a mobile platform, SURTASS greatly increases the area where submarines can be found. The combined SURTASS and SOSUS systems are part of the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS). By the end of the Cold War in the late 1980’s, the ability of passive acoustics to detect and track Soviet nuclear submarines at long ranges had decreased significantly. Modern diesel-electric submarines are quieter and more difficult to detect by passive listening.

IUSS in the late 1980s. The black stars represent NAVFAC or NOPF sites; the two white stars represent the Ocean System Commands. IUSS-CAESAR Alumni Association (https://www.iusscaa.org/).

In the 1990s, the classified SOSUS network was opened to scientists with security clearances to study marine mammals and ambient noise conditions. Published scientific papers demonstrate the ocean basin scale and long-term time series research that can be conducted with SOSUS.

The Navy can also use active acoustics to find submarines much the same way people use active acoustics to find fish (See “How is sound used to locate fish?“). By transmitting a sound pulse and receiving the echo on an array, the sonars can determine the direction of the echoes that return from objects hit by the sound. They can also measure the time it takes for echoes to return and calculate the distance to the object causing the echo. A skilled sonar operator or a computer program can distinguish submarine echoes from those of ocean bottom features, whales, schools of fish, etc. Much research continues to be done on classifying the kinds of echoes that different objects make.

There are basically two types of active acoustic systems employed by navies around the world. Low frequency sonars are used for long-range (on the order of hundreds of kilometers) surveillance. The U.S. Navy has developed the SURTASS LFA (Low Frequency Active) system that uses a vertical array of 18 projectors to transmit signals in the 100-500 Hz frequency range, with the echoes received by the SURTASS towed array. The source level of each projector is approximately 215 underwater dB at 1 m; the entire projector array has an effective source level from 230 to 240 underwater dB at 1 m.

Sonars that operate at frequencies of 2-10 kHz are used to find and track underwater targets at ranges of tens of kilometers. In the U.S. these are called “mid-frequency sonars” while they may be called “low frequency sonars” in other countries. One U.S. mid-frequency sonar system (AN/SQS-53C), housed in a bulbous dome mounted on the hull of a ship, uses pulses centered at 2.6-3.3 kHz (and ranging from 1-5 kHz), with effective source levels of 235 underwater dB at 1 m with ping lengths of approximately 1-3 sec. One controversial and unresolved issue is how the use of mid-frequency military sonar relates to strandings of marine mammals, particularly strandings of some species of beaked whales.

Sonobuoy being loaded into aircraft. (U.S. Navy Imagery used on this website without endorsement expressed or implied.)

Another acoustics system for assisting with antisubmarine warfare is the U.S. Navy’s sonobuoy system. Sonobuoys use a transducer and a radio transmitter to record and transmit underwater sounds. Aircraft can drop these instruments into the water from altitudes as high as 30,000 feet. Once a sonobuoy reaches the water, it deploys an inflatable surface float with a radio transmitter to communicate with the aircraft and the transducer descends below the sea surface to a selected water depth. Multiple sonobuoys can be deployed in a pattern to determine the exact location of a target.

The Directional Frequency Analysis and Recording (DIFAR) sonobuoy is a passive acoustic sonobuoy used by the Navy to detect underwater submarines. DIFAR buoys include one or more vector sensors that give the direction to the source of an acoustic signal. They also typically include non-directional hydrophones. DIFAR sonobuoys detect acoustic energy from 5 to 2,400 Hz and can operate for up to eight hours at depths of up to 305 m (1000 ft). These sonobuoys have also been used for research to track whale populations and monitor underwater volcanic activity.

The Directional Command Activated Sonobuoy System (DICASS) sonobuoy is an active acoustic sonobuoy used by the Navy to detect submarines. The “command activated” part of the system allows DICASS buoys to receive radio transmissions instructing the buoy to change depth, activate sonar transmissions, or scuttle tself. Active sonar pulses can be transmitted at four frequencies (6.5 kHz, 7.5 kHz, 8.5 kHz, and 9.5 kHz) and can operate for up to one hour at depths of up to 457 m (1,500 ft). The echo returns of the active sonar signals provide range, bearing, and Doppler information on acoustic contacts.

Additional Links on DOSITS

- Science of Sound > The Cold War: History of the SOund SUrveillance System (SOSUS)

- Science of Sound > What are common underwater sounds?

- People and Sound > How is sound used to locate fish?

- Technology Gallery > Sonobuoys

- Technology Gallery > Hydrophone Arrays

- Technology Gallery > Projector Array

- Technology Gallery > Sonar

- Technology Gallery > Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS)

- Technology Gallery > Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System Low Frequency Active (SURTASS LFA) Sonar

Additional Resources

- Department of Navy – SURTASS LFA.

- National Museum of American History – Sonar Room.

- NOAA PMEL – Acoustic Monitoring, SOund SUrveillance System (SOSUS)

- Ocean Explorer – Technologies for Ocean Acoustic Monitoring.

- Bill Cabbage, ORNL and Submarines – Measuring the Sound of Silence.

- Federation of American Scientists (FAS), Run Silent, Run Deep.

- Dr. Owen R. Cote, Jr. 3/1/2000, The Third Battle: Innovation in the U.S. Navy’s Silent Cold War Struggle with Soviet Submarines. MIT Security Studies Program, March 2000.

- Wolf, G. 11/1998, U.S. Navy Sonobuoys – Key to Antisubmarine Warfare. 1998. Sea Technology. p.41-44.

- Whale Acoustics- DIFAR Sonobuoys (Wayback Machine).

References

- Amato, I. (1993). A sub surveillance network becomes a window on whales. Science, 261(5121), 549–550. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.261.5121.549

- Andrew, R. K., Howe, B. M., Mercer, J. A., & Dzieciuch, M. A. (2002). Ocean ambient sound: Comparing the 1960s with the 1990s for a receiver off the California coast. Acoustics Research Letters Online, 3(2), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1461915

- Charif, R. A., Clapham, P. J., & Clark, C. W. (2001). Acoustic detections of singing humpback whales in deep waters off the British Isles. Marine Mammal Science, 17(4), 751–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01297.x

- Stafford, K. M., Nieukirk, S. L., & Fox, C. G. (2001). Geographic and seasonal variation of blue whale calls in the North Pacific. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 3(1), 65–76.

- Watkins, W., Daher, M. A., Reppucci, G., George, J., Martin, D., DiMarzio, N., & Gannon, D. (2000). Seasonality and Distribution of Whale Calls in the North Pacific. Oceanography, 13(1), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2000.54

- Wit, J. S. (1981). Advances in antisubmarine warfare. Scientific American, 244(2), 31–41.