Tutorial: Pile Driving

Installing large structures in shallow marine environments requires the insertion into the seabed of support elements, called piles, made of wood, steel, or reinforced concrete. These piles, once installed, extend from above the water surface to as much as several hundred feet below the seabed. Installing the piles may require impact pile driving, which uses a hydraulic hammer to repeatedly strike the top of the pile, pushing it into the seafloor. The blows are delivered approximately once per second. Depending on the size of the hammer, bottom properties, and the required penetration depth, it may take several hours and as many as 5,000 strikes to drive one pile into the seabed.

Pile driving associated with wind farm construction off the coast of Block Island, Rhode Island. Photo courtesy of Dr. Kathleen Vigness-Raposa.

Impact pile driving produces intense, broadband impulsive sounds that can propagate many kilometers. Near source (within 10 m of the pile driving activities) sound pressure levels (SPLs) range up to 220 dB peak, but vary substantially according to the size of the hammer, power of the hammer, pile material, diameter of the pile, as well as properties of the seafloor.

Two criteria for assessing the potential impacts of pile driving sounds are: 1) SPL peak and 2) cumulative sound exposure level (SELcum). For more information, please see the Advanced Topic on Sound Pressure Levels and Sound Exposure Levels.

To investigate the potential effects of pile driving on fishes, several species of freshwater fish were exposed in a chamber to simulated pile driving sounds. The scientists reported that injuries varied according to the peak pressure, number of strikes, the species of fish, and whether a fish had a swim bladder. The scientists found that at the lowest sound pressure levels and fewest number of pile strikes there were no detectable injuries. Injuries reported included damage to hair cells, swim bladders, and soft tissues, according to the exposure level.

These studies were conducted in a laboratory setting and research is still needed on free-swimming animals to determine the potential for injuries on fishes in the wild from pile driving sounds. It is not known how the sounds of a pile driving operation will affect fish behavior or mask hearing of biologically relevant sounds.

Marine Mammals

Most research on potential effects of pile driving on marine mammals has been conducted in European waters in association with the development of offshore wind farms. Potential effects have been investigated on several cetacean and pinniped species.

Research results have shown that pile driving sounds may cause temporary threshold shift (TTS) or permanent threshold shift (PTS). Scientists measured pile driving sounds during construction of a wind farm off the northeast coast of Scotland. Although the levels to cause PTS have not been directly measured, based on the regulatory criteria currently in use[1]Southall, B. L., Bowles, A. E., Ellison, W. T., Finneran, J. J., Gentry, R. L., Greene, C. R., … Tyack, P. L. (2007). Marine mammal noise exposure criteria: Initial scientific recommendations. Aquatic Mammals, 33(4), 411–414. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.33.4.2007.411, broadband peak-to-peak sound levels consistent with TTS onset would have been exceeded for cetaceans within 10 m of the pile driving operations and within 40 m for pinnipeds. The level estimated to cause PTS onset would occur within 5 m for cetaceans and 20 m for pinnipeds. Scientists determined that no form of injury or hearing impairment would occur at ranges greater than 100 m.

Observed behavioral responses in response to pile driving include changes in direction, swimming speed, dive profiles, group movements, vocalizations, and respiration rates. There are concerns that avoidance responses to pile driving can impact foraging, nursing, and/or mating activities, and therefore overall fitness, of a marine mammal.

Mitigation Measures

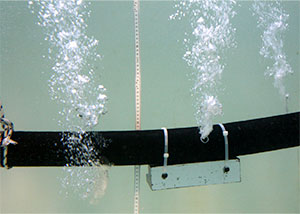

Various mitigation measures, such as bubble curtains, screens, or cofferdams (an insulating sleeve around the pile), have been developed to diminish the potential impacts of pile driving on marine life. Acoustic deterrent devices have also been deployed prior to pile driving activities at many European wind farm sites in order to deter marine mammals from entering the construction zone. Pile driving activities may also begin with a “ramp-up” or “soft start” where lower hammer energy levels are used to start the pile driving process, and then the force of pile driving is gradually increased.

Listen to the sound below to hear pile driving activity before and after a bubble curtain system is activated. Please note, this sound recording demonstrates the effectiveness of this mitigation option and is not meant to demonstrate how it is actually done (e.g., the bubble curtain would already be up and operational before any piling started in a real-world scenario)

Sound recording of 36 inch diameter steel pipe (1” wall thickness) being driven by a diesel impact hammer at a water depth of 7.5m. Approximately midway through the recording, a dual-ring bubble curtain (400 cubic ft per minute flow rate, 75 psi air pressure) is activated. One should be able to hear a difference in the pile-driving sounds before and after the bubble curtain is activated. The sound were recorded by a hydrophone in 20m of water, approximately 1m above the seabed.

Courtesy of Connor, Heithaus, Berggren and Miksis.

Close-up view of a bubble curtain in operation. One can see the streams of bubbles exiting the hose of the bubble curtain. Image courtesy of Georg Nehls.

Anthropogenic Sound Sources Tutorial Sections:

Additional Links on DOSITS

- Behavioral Changes in Mammals

- Behavioral Changes in Fishes

- Bubble Curtain

- How is sound used to protect marine mammals?

- Masking

- Moderate or eliminate the effects of human activities

- Pile-driving

- Sound Pressure Levels and Sound Exposure Levels

- Wind Turbines

Additional Resources

- Halvorsen, M. B., Casper, B. M., Woodley, C. M., Carlson, T. J., & Popper, A. N. (2011). Predicting and mitigating hydroacoustic impacts on fish from pile installations. NCHRP Research Results Digest 363, Project 25-28. Washington, D.C.: National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board,National Academies Press. (Publication Link)

- Dahl, P. H., de Jong, C. A. F., & Popper, A. N. (2015). The Underwater Sound Field from Impact Pile Driving and Its Potential Effects on Marine Life. Acoustics Today, 11(2), 18–25. (PDF)

- De Jong, C. A. F., & Ainslie, M. A. (2008). Underwater radiated noise due to the piling for the Q7 Offshore Wind Park. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 123(5), 2987–2987. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2932518

References

- Bailey, H., Brookes, K. L., & Thompson, P. M. (2014). Assessing environmental impacts of offshore wind farms: lessons learned and recommendations for the future. Aquatic Biosystems, 10(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-9063-10-8

- Bailey, H., Senior, B., Simmons, D., Rusin, J., Picken, G., & Thompson, P. M. (2010). Assessing underwater noise levels during pile-driving at an offshore windfarm and its potential effects on marine mammals. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 60(6), 888–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.01.003

- Brandt, M., Diederichs, A., Betke, K., & Nehls, G. (2011). Responses of harbour porpoises to pile driving at the Horns Rev II offshore wind farm in the Danish North Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 421, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08888

- Casper, B. M., Halvorsen, M. B., Matthews, F., Carlson, T. J., & Popper, A. N. (2013). Recovery of barotrauma injuries resulting from exposure to pile driving sound in two sizes of hybrid striped bass. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e73844. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073844

- Casper, B. M., Smith, M. E., Halvorsen, M. B., Sun, H., Carlson, T. J., & Popper, A. N. (2013). Effects of exposure to pile driving sounds on fish inner ear tissues. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 166(2), 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.07.008

- Dolman, S., & Simmonds, M. (2010). Towards best environmental practice for cetacean conservation in developing Scotland’s marine renewable energy. Marine Policy, 34(5), 1021–1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.02.009

- Haelters, J., Dulière, V., Vigin, L., & Degraer, S. (2015). Towards a numerical model to simulate the observed displacement of harbour porpoises Phocoena phocoena due to pile driving in Belgian waters. Hydrobiologia, 756(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-014-2138-4

- Halvorsen, M. B., Casper, B. M., Matthews, F., Carlson, T. J., & Popper, A. N. (2012). Effects of exposure to pile-driving sounds on the lake sturgeon, Nile tilapia and hogchoker. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1748), 4705–4714. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.1544

- Halvorsen, M. B., Casper, B. M., Woodley, C. M., Carlson, T. J., & Popper, A. N. (2012). Threshold for Onset of Injury in Chinook Salmon from Exposure to Impulsive Pile Driving Sounds. PLoS ONE, 7(6), e38968. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038968

- Hastie, G. D., Russell, D. J. F., McConnell, B., Moss, S., Thompson, D., & Janik, V. M. (2015). Sound exposure in harbour seals during the installation of an offshore wind farm: predictions of auditory damage. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(3), 631–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12403

- Kastelein, R. A., Gransier, R., Marijt, M. A. T., & Hoek, L. (2015). Hearing frequency thresholds of harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena ) temporarily affected by played back offshore pile driving sounds. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 137(2), 556–564. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4906261

- Kastelein, R. A., Schop, J., Gransier, R., & Hoek, L. (2014). Frequency of greatest temporary hearing threshold shift in harbor porpoises ( Phocoena phocoena ) depends on the noise level. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 136(3), 1410–1418. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4892794

- Kastelein, R. A., van Heerden, D., Gransier, R., & Hoek, L. (2013). Behavioral responses of a harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) to playbacks of broadband pile driving sounds. Marine Environmental Research, 92, 206–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2013.09.020

- Madsen, P., Wahlberg, M., Tougaard, J., Lucke, K., & Tyack, P. (2006). Wind turbine underwater noise and marine mammals: implications of current knowledge and data needs. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 309, 279–295. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps309279

- Reyff, J. (2012). Underwater Sounds From Unattenuated and Attenuated Marine Pile Driving. In A. N. Popper & A. Hawkins (Eds.), The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life (Vol. 730, pp. 439–444). New York, NY: Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7311-5_99

- Smith, M. E., Coffin, A. B., Miller, D. L., & Popper, A. N. (2006). Anatomical and functional recovery of the goldfish (Carassius auratus) ear following noise exposure. Journal of Experimental Biology, 209(21), 4193–4202. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.02490

- Teilmann, J., & Carstensen, J. (2012). Negative long term effects on harbour porpoises from a large scale offshore wind farm in the Baltic—evidence of slow recovery. Environmental Research Letters, 7(4), 045101. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/045101

- Thompson, P. M., Lusseau, D., Barton, T., Simmons, D., Rusin, J., & Bailey, H. (2010). Assessing the responses of coastal cetaceans to the construction of offshore wind turbines. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 60(8), 1200–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.03.030

- Tougaard, J., Carstensen, J., Teilmann, J., Skov, H., & Rasmussen, P. (2009). Pile driving zone of responsiveness extends beyond 20 km for harbor porpoises ( Phocoena phocoena (L.)). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 126(1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3132523

Cited References

| ⇡1 | Southall, B. L., Bowles, A. E., Ellison, W. T., Finneran, J. J., Gentry, R. L., Greene, C. R., … Tyack, P. L. (2007). Marine mammal noise exposure criteria: Initial scientific recommendations. Aquatic Mammals, 33(4), 411–414. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.33.4.2007.411 |

|---|