How do sea turtles hear?

Olive ridley sea turtle nesting on a beach in Guatemala. Photo courtesy of Scott Handy, Pacuare Reserve, Costa Rica.

Sea turtles are found throughout the Ocean. There are seven sea turtle species: the green turtle (Chelonia mydas), flatback (Natator depressus), loggerhead (Caretta caretta), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempi), and leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea).

Turtle sounds have been recorded during sea turtle nesting. Sea turtles lay eggs on land. Mating takes place at sea, but female sea turtles come ashore to lay their eggs. Most females return to the beach where they were hatched. Females dig a nest in sand up to one meter deep and lay then bury a clutch of 50–130 eggs in the nest. The eggs then incubate in the nests for 40–70 days (McKenna et al. 2019). Sounds that females produce during the egg-laying process include heavy breathing and grunting (Cook and Forrest 2005).

Sounds from hatchlings have been recorded in the nest during incubation, hatching, and emergence (Ferrara et al. 2014, 2019). Hatchlings typically emerge from nests at about the same time at night and make their way to the ocean. It is debatable whether sounds play a role in the synchronization of hatching or emergence (Monteiro et al. 2019; McKenna et al. 2019). Hatchling vocalizations have also been recorded after emerging from the nest (McKenna et al. 2019).

Ten different green turtle sounds were recorded using acoustic data loggers attached to the shells of eleven juvenile green turtles in a bay off the coast of Martinique (Charrier et al. 2022). The frequencies of the recorded sounds fall within the reported hearing ranges of juvenile green turtles.

This is an emerging field of research and additional research is needed to understand the communication function of both the in-air and underwater vocalizations that have been recorded.

What do we know about sea turtle hearing?

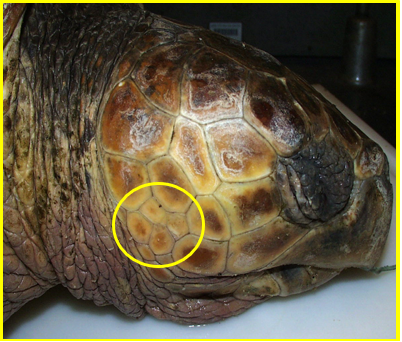

Sea turtle ears and the ears in some freshwater turtles have a relatively simple structure similar to that of birds but with adaptations for underwater sound detection. The external surface of a sea turtle’s ear is covered by a ring of scales (cutaneous plates) that are smaller than those on the rest of the head as shown below (Wever 1978; Piniak et al. 2016).

Smaller ring of scales (cutaneous plates; circled in yellow, left image) that covers the opening to the middle ear (circled in red, right image) in the head of a loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta). Image credit: Darlene Ketten, WHOI.

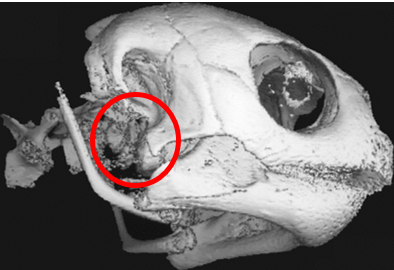

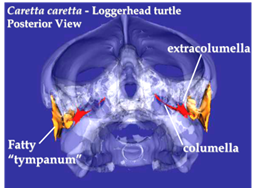

Underneath the scales is a fatty cone (tympanum) that connects with the middle ear cavity and provides good tissue conduction for underwater sound (see figure below). The tympanum connects to a cartilaginous shaft that consists of the extracolumella and the columella and acts like a stapes in mammals. The large, cone-shaped footplate of the columella is connected by stapedo-saccular strands to the saccule, relaying vibrational energy that stimulates hair cells located in the inner ear.

A composite 3D reconstruction of a CT of the skull and MRI of the ear soft tissues in the head of a loggerhead turtle. Credit: Darlene Ketten, WHOI.

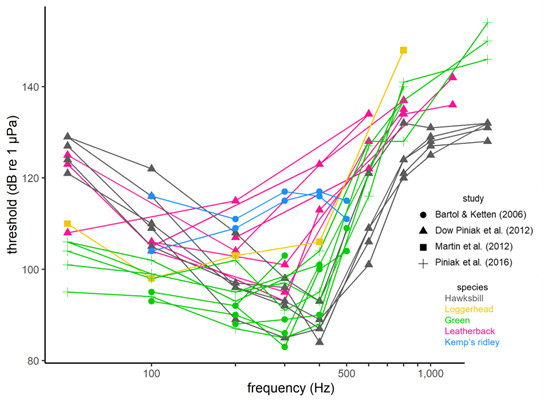

Hearing sensitivity studies have been conducted with sea turtles, though whether sea turtles respond to pressure, particle motion, or both, remains poorly understood (Piniak et al. 2016). Hearing sensitivity of sea turtles has also been shown to change significantly with age (Bartol and Ketten 2006). The hearing of juvenile turtles is broader (spans more frequencies) and more sensitive than adult turtles (Bartol and Ketten 2006; Martin et al. 2012; Piniak et al. 2012, 2016; DoN 2024; Ridgway et al. 1969). The hearing of green, hawksbill, Kemp’s ridley, leatherback, and loggerhead sea turtles has been tested between 50 and 1,600 Hz, with best hearing between 100 and 800 Hz, as seen in the audiogram figure below (Bartol and Ketten 2006; Martin et al. 2012; Piniak et al. 2012, 2016; DoN 2024). Five juvenile green sea turtles were tested between 50 Hz and 1,600 Hz, with maximum sensitivity between 200 and 400 Hz (Piniak et al. 2016). Juvenile green turtles were more sensitive to in-air acoustic stimuli, but their in-air hearing frequencies were more limited. When comparing sensitivities measured with behavioral studies or auditory evoked potentials (AEPs), loggerhead turtles responded to underwater signals between 50 and 1,131 Hz, with best sensitivity at 100 Hz using behavioral methods and between 200 and 400 Hz using AEP (Martin et al. 2012).

Audiograms of sea turtle hearing sensitivity. Each line represents an individual turtle. Each symbol denotes the study. Each color shows a different species: hawksbill in gray (n=5), loggerhead in yellow (n=1), green in green (n=9), leatherback in pink (n=7), and Kemp’s ridley in blue (n=2). (Modified from Department of the Navy 2024 Phase 4 Criteria Report).

Studies are ongoing to understand the potential effects to sea turtles from exposure to underwater sound. Sea turtles appear to be sensitive to low-frequency sounds, though with much less sensitivity than marine mammals or fishes.

Additional Resources

- NOAA Fisheries: Sea Turtles in a Sea of Sound https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/sea-turtles-sea-sound

- IOSEA Marine Turtles https://www.cms.int/iosea-turtles/en/page/marine-turtles-and-underwater-noise

- University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill: Sea Turtle Secrets https://endeavors.unc.edu/sea-turtle-secrets/

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Computerized Scanning and Imaging Facility https://csi.whoi.edu/

- Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission Sea Turtle Program: https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/sea-turtle/

References

- Bartol, S. M., & Ketten, D. R. (2006). Turtle and Tuna Hearing. In: Sea Turtle and Pelagic Fish Sensory Biology: Developing Techniques to Reduce Sea Turtle Bycatch in Longline Fisheries, Swimmer, Y., & Brill, R. (eds). NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-PIFSC-7.

https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/3508 - Bartol, S. M., Musick, J. A., & Lenhardt, M. L. (1999). Auditory Evoked Potentials of the Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta). Copeia, 1999(3), 836. https://doi.org/10.2307/1447625

- Charrier, I., Jeantet, L., Maucourt, L., Régis, S., Lecerf, N., Benhalilou, A., & Chevallier, D. (2022). First evidence of underwater vocalizations in green sea turtles Chelonia mydas. Endangered Species Research, 48, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01185

- Cook, S. L., & Forrest, T. G. (2005). Sounds produced by nesting leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Herpetological Review, 36(4), 387–390.

- Department of the Navy (DoN). (2024). Criteria and thresholds for U.S. Navy acoustic and explosive effects analysis (Phase 4) (p. 236). https://www.nepa.navy.mil/Portals/20/Documents/aftteis4/Criteria%20and%20Thresholds%20for%20U.S.%20Navy%20Acoustic%20and%20Explosive%20Effects%20Analysis%20(Phase%20IV).pdf

- Ferrara, C. R., Vogt, R. C., Sousa-Lima, R. S., Lenz, A., & Morales-Mávil, J. E. (2019). Sound Communication in Embryos and Hatchlings of Lepidochelys kempii. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 18(2), 279. https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-1386.1

- Ketten, D. R., & Bartol, S. M. (2005). Functional Measures of Sea Turtle Hearing. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution: ONR Award No: N00014-02-1-0510.

- Lavender AL, Bartol SM, Bartol IK (2014) Ontogenetic investigation of underwater hearing capabilities in loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) using a dual testing approach. J Exp Biol 217:2580±2589. doi: 10.1242/jeb.096651 PMID: 24855679

- Martin KJ, Alessi SC, Gaspard JC, Tucker AD, Bauer GB, Mann DA (2012) Underwater hearing in the loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta): a comparison of behavioural and auditory evoked potential audiograms. J Exp Biol 215:3001±3009. doi: 10.1242/jeb.066324 PMID: 22875768

- McKenna, L. N., Paladino, F. V., Tomillo, P. S., & Robinson, N. J. (2019). Do Sea Turtles Vocalize to Synchronize Hatching or Nest Emergence? Copeia, 107(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1643/CE-18-069

- Monteiro, Cibele C., Carmo, Hayane M.A., Santos, Armando J.B., Corso, Gilberto, and Sousa-Lima, Renata S. 2019. First Record of Bioacoustic Emission in Embryos and Hatchlings of Hawksbill Sea Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata).Chelonian Conservation and Biology 18(2), 273-278 https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-1382.1

- Piniak, W. E. D., Eckert, S. A., Harms, C. A., & Stringer, E. M. (2012). Underwater hearing sensitivity of the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea): Assessing the potential effect of anthropogenic noise (p. 35). U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

- Piniak, W. E. D., Mann, D. A., Harms, C. A., Jones, T. T., & Eckert, S. A. (2016). Hearing in the Juvenile Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas): A Comparison of Underwater and Aerial Hearing Using Auditory Evoked Potentials. PLOS ONE, 11(10), e0159711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159711

- Ridgway, S. H., Wever, E. G., McCormick, J. G., Palin, J., & Anderson, J. H. (1969). Hearing in the giant sea turtle, Chelonia mydas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 64(3), 884–890.

- Salas, A.K., Capuano, A.M., Harms, C.A., Piniak, W.E.D., Mooney, T.A. (2023). Calculating Underwater Auditory Thresholds in the Freshwater Turtle Trachemys scripta elegans. In: Popper, A.N., Sisneros, J., Hawkins, A.D., Thomsen, F. (eds) The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10417-6_142-1

- Salas, A.K., Capuano, A.M., Harms, C.A., Piniak, W.E.D., Mooney, T.A. (2023). Temporary noise-induced underwater hearing loss in an aquatic turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans). Acoust. Soc. Am.1 August 2023; 154 (2): 1003–1017. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0020588

- Wever, E. G. 1978. The Reptile Ear: Its Structure and Function. Princeton University Press, Princeton.